Few can claim to have lost their country. Even fewer can claim to have lost their chance for a peaceful return. Exiled independent Russian journalist Elena Kostyuchenko has lost both. Originally hailing from Yaroslavl, Russia, Kostyuchenko began her career in journalism by working for her local paper. She later studied journalism at Moscow State University and interned at Novaya Gazeta, a paper critical of the government under President Vladimir Putin’s control.

After graduation, Kostyuchenko joined Novaya Gazeta’s staff as a full-time writer, covering stories about “the lesser known” parts of Russia spanning from small villages to state-run mental institutions. In addition to her journalism work, Kostyuchenko often openly discusses her lesbian identity and frequently involves herself with LGBTQIA street activism, attempting to celebrate and make Russia’s LGBTQIA community visible.

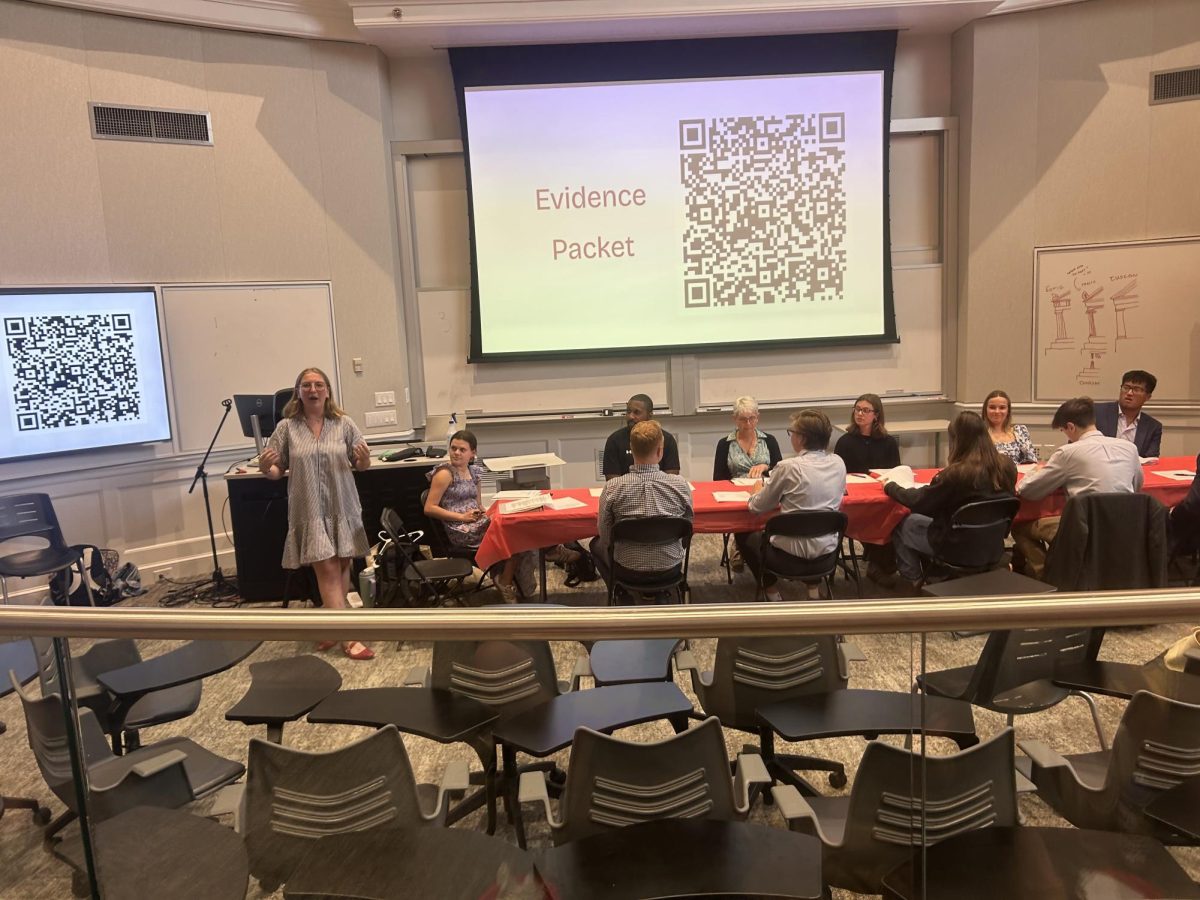

Kostyuchenko came to Davidson on October 29th on behalf of the Dean Rusk International Studies Program by the recommendation of Chair & Professor of Russian Studies Dr. Amanda Ewington as part of the Dean Rusk Lecture Series. The conversation about inviting her to speak at Davidson began last February. “Larisa Ivanovna and I had been talking about our concern that our Russian [language and literature] students were not very familiar with what was going on in contemporary Russia in terms of culture, opposition, politics, and news,” Dr. Ewington shared.

During her two-day stay, Kostyuchenko met with both a Gender and Sexuality Studies class and Dr. Ewington’s Russian literature class. In Dr. Ewington’s class, Kostyuchenko read a chapter from her new book, I Love Russia: Reporting From a Lost Country. “[She] talked to them about the history of the idea of madness in Russian literature, and the way throwing people in mental asylums and declaring them mad has been also a strategy [used] against dissidents […] by the Russian state and the Soviet state,” Dr. Ewington stated.

Despite her book’s title, Kostyuchenko’s “love” for her home country is complicated. “When I say I love Russia, I mean Russia as [a collective]—many people living there united [through a] common destiny, and not always a good destiny, but still common. And when I say love, I mean the feeling of belonging,” Kostyuchenko explained. “I feel like I belong to these people, and they belong to me, and [we] are united in some strange way.”

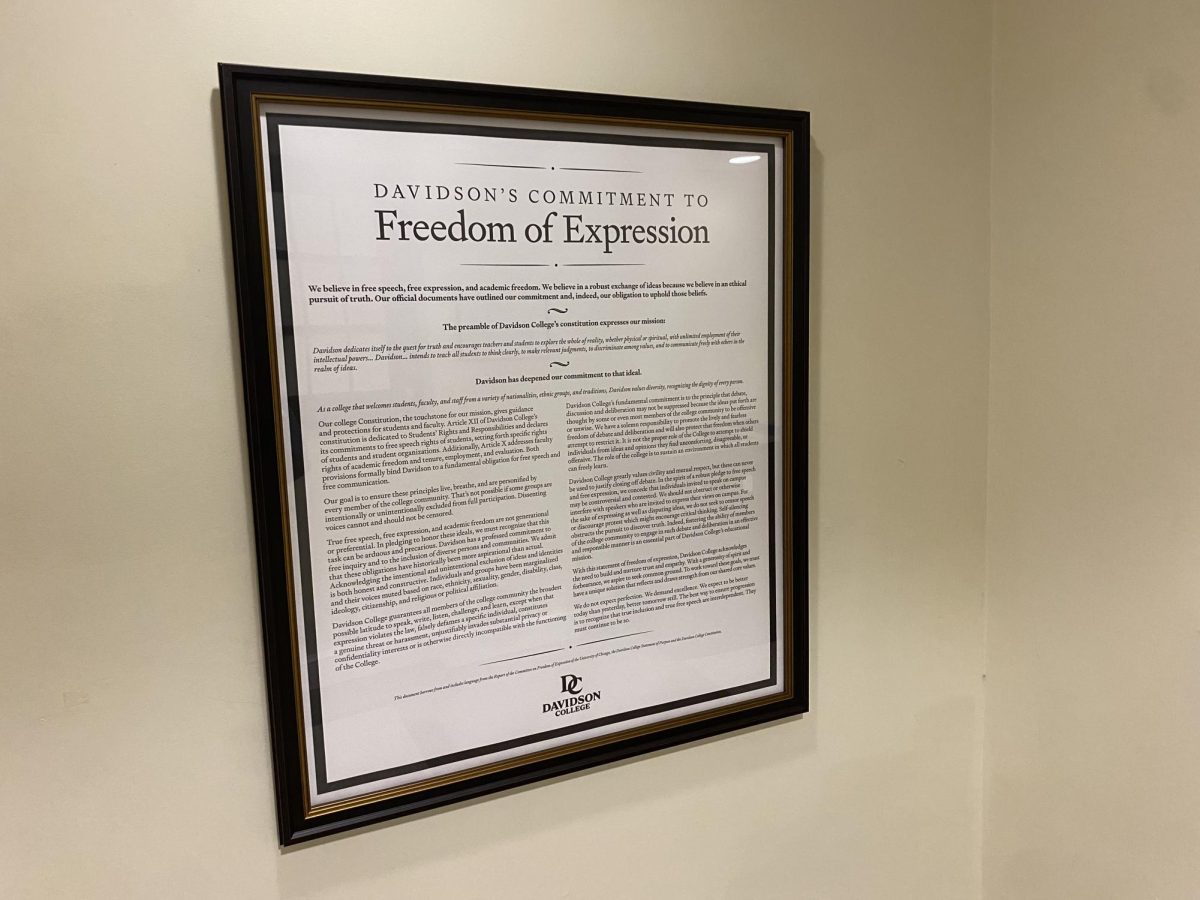

Kostyuchenko’s love for Russia differs drastically from the one pushed by President Putin in state media. “He basically says that if you love Russia, you need to go kill Ukrainians […] if you love Russia, you should obey, be silent, or lie if you need to. But the truth is that love doesn’t demand any murders or lies or silence,” Kostyuchenko declared in her lecture.

On the war in Ukraine, Kostyuchenko admitted, “I’m a reporter. I reported on Russia all my life, and I didn’t see this war coming. And then I realized that the very same love, which gave me energy to work […] also gave me hope. And this hope blinded me.”

Kostyuchenko’s work has put her life in danger. According to a blog post by Kostyuchenko on independent Russia media outlet Meduza, she was living in exile in Berlin, Germany when she was warned of Russian plans to assassinate her. Soon after, she was on her way back from a trip to Munich to apply for a Ukrainian visa when she began to sweat and develop a headache. Her symptoms only got worse when she arrived home, as she developed abdominal pain and nausea. Nearly two months later, after multiple rounds of testing and fluctuations in her symptoms, Kostyuchenko contacted the police and underwent questioning for a poison investigation. “I contacted the police and got a hospital referral. The detectives followed me to the clinic, where they questioned me as well as the physicians,” she described in her blog post.

While the poisoning was never officially confirmed, Kostyuchenko understood that she needed to be careful moving forward. “I realized that I cannot do [reporting] the same way I did all my life—hiding behind a character’s back, never [being] present on the page. I realized that if I write about rising fascism Russia, I need to investigate my own […] life too, because I’m a part of this picture.”In order to make up for what she thought her journalism was lacking, Kostyuchenko turned to activism.

In her lecture, she emphasized the good work many other organizations across Russia are undertaking, work that rarely reaches the eyes and ears of Americans or other foreign observers.

“There are many people who do better work than I do. […] Right now, I’m collaborating with a group of four hundred lesbians [all over] Russia,” Kostyuchenko stated after the lecture. “And this group was created after the full-scale invasion [of Ukraine], and after all this crazy legislation against [the LGBTQIA community] was applied. And they’re doing different things […] but basically, they’re helping each other survive.”

Kostyuchenko and her work are a part of a wider resistance movement. She is part of a collective that ranges from grade school teachers trying to counter pro-Putin propaganda in schools to women covertly raising funds for Russian soldiers to desert to LGBTQIA activists continuing the fight within Russia. She is one small voice in a chorus of a thousand unsung heroes. “My love to Russia hurts a lot, but still, I don’t want to refuse this feeling, because I do believe that love has a greater power in the universe, and it even can conquer death,” she said.