Art has long served as a form of commemoration. Davidson engaged deeply with this form of remembrance during last week’s dedication of “With These Hands: A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited.” Art, in the form of the two work-worn hands of cast bronze, was used as a medium to interrogate and reckon with themes of oppression, erasure and belonging, both on and off Davidson’s campus. The final form that this commemoration would take was years in the making.

Lia Newman, director and curator of Davidson’s art galleries, was a staff liaison to the Commemoration Committee that convened in December 2020. Newman guided the Committee’s early stage of determining the key characteristics for a memorial at Davidson, alongside professors Hilary Green and Cort Savage.

“[We went] through a series of questions to think about […] what were the characteristics of those memorials that made you feel changed when you left […] and in particular, what was it that helped you feel connected to an experience that was not your own, when the memorial was not about your family’s history,” Newman said.

The potential design teams hosted community engagement sessions to gather input from alumni, faculty, staff and residents. These sessions clarified Newman’s own understanding of how the memorial would function in the broader community.

“One of the community members asked one of the architects on a different team, ‘Tell me how I explain that to my eight-year old granddaughter.’ It was a [reminder that] This is not a project for us. This is a project for the community,’” Newman said.

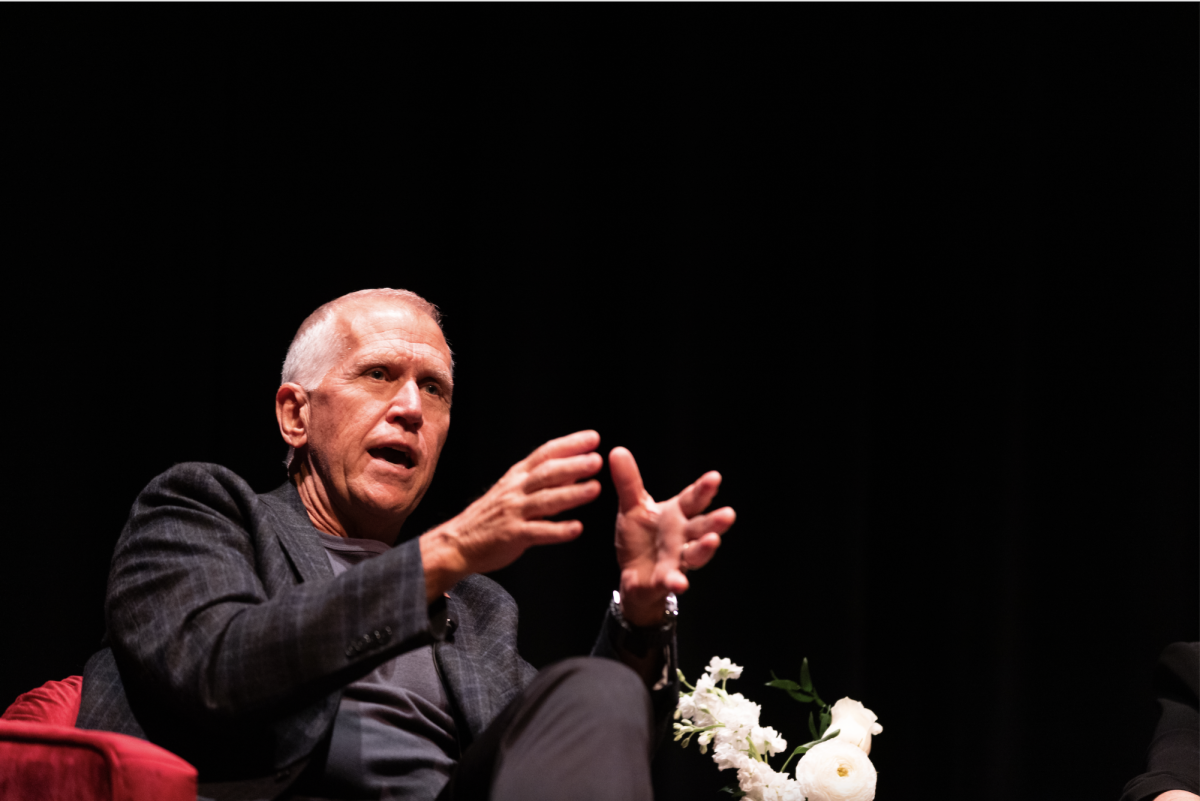

Initially, Newman felt more drawn to conceptual designs than those with figurative elements. The community’s interest in a memorial with direct symbolism, however, led to the jury’s selection of Hank Willis Thomas with Perkins&Will to design the memorial.

“This piece was a really direct way for people to say: ‘Black people built the campus. They labored here, they physically made the bricks, they built the buildings, they did the laundry, they took care of people, they worked in chemistry labs. […] They worked and were not credited,’” Newman said.

The memorial navigates a tension between symbolism and specificity. The sculpture embodies “generations of people in one figurative gesture,” Newman said, in a way that might appear to contradict the College’s efforts to name and document the stories of specific individuals. On the other hand, the sculpture’s androgynous hands can also be understood as an acknowledgment that it may be impossible to identify every individual deserving of recognition.

“[In one of our early meetings] someone said, ‘Doesn’t that feel really masculine? A lot of the labor here was done by women.’ And someone else in the room said, ‘My grandmother was a laborer and her hands looked exactly like that. I never thought that those [hands] were masculine. […] I never viewed his sculpture as being […] gendered in that way,’” Newman said.

Moments like this reminded Newman that every viewing experience is uniquely informed by each individual’s specific background. “It’s sort of about your experience and […] hopefully you see what you see in it, you understand it as you understand it,” Newman said.

The physical experience of taking in the hands can also affect the sculpture’s impact. Newman pointed to the difference in distance between the hands at the two entry/exit points. “Your experience coming in and out is a little bit different. […] If you’re entering from the wrists, you might walk in with people; but when you exit—if you exit by the pinkies—it’s a tighter space so you might exit alone,” Newman said.

The memorial’s location was intentional: it sits adjacent to Main Street, the western edge of Davidson’s campus that separates it from predominantly Black West Davidson. Bowles said she hopes that the memorial can serve as a bridge between campus and the broader Davidson community.

The location is also significant when considering how different community members move through ‘communal’ space. “It was made so that people who did not feel welcome previously did not feel like they had to go deep into campus to get to this memorial that is supposed to be about their family,” Newman said.

Vann Professor of Racial Justice Laurian Bowles was a member of the Commission on Race and Slavery that recommended the College create a visible acknowledgement to the enslaved and exploited on campus. She emphasized that completing the memorial does not mean the College’s work is done.

“We started this work seven years ago. It just is really incredible to be a part of this and I really appreciate that even between administrations—different presidents, different deans—that at least the sentiment and the ethos of the conversation is: this is the beginning.”

“The idea of art as a provocation for a conversation, can be described as foo foo, but really I think this memorial will hopefully raise people’s consciousness about the naming conventions, art conventions, and what the power of art is,” Bowles said.