The Davidson Visual Arts Center’s (VAC) new exhibit titled “We the People,” opened this past Friday, Oct. 10. The featured artist, Hank Willis Thomas, also created the memorial to the enslaved and exploited people who built Davidson’s campus—“With These Hands”—which is set to be unveiled on Oct. 23rd.

The exhibit in the VAC was designed to augment and exist in conversation with the memorial. Director & Curator of Art Gallery Lia Newman helped arrange the pieces.

“We really tried to choose his works that best supported the themes and stories of the memorial,” she said. Many of these themes are present in the artist’s broader practice, including identity, collective memory and the legacy of exploitation and exclusion, but also hope, reconciliation and inclusion.

Some of the many subjects of analysis in the exhibit include gun rights, exclusion and the erasure of history, among many other contemporary and controversial issues both across the country and on Davidson’s campus.

The exhibit, along with the memorial, was created in collaboration with the gallery’s faculty, the Davidson Commission on Race and Slavery, students, staff and faculty, as well as descendants of those who were enslaved and exploited by Davidson College.

Immediately upon entering the exhibit, the diversity in media is striking. “He chooses the best medium to communicate whatever it is that he wants to say, allowing him to span many mediums, genres, and subjects,” Newman said.

Thomas’ art is unique in form and appearance—particularly for a solo artist—as he utilises mediums including sculpture, retroflective vinyl and lenticular works, textiles and neon.

With a plethora of sculpture and color, the art fills the space of the gallery, which Newman explained was a very intentional choice. “Perspective is a really key part of this exhibition, and it’s the literal and physical perspective he was playing with mostly. So, we wanted a really bold and full physical experience in the gallery,” Newman said.

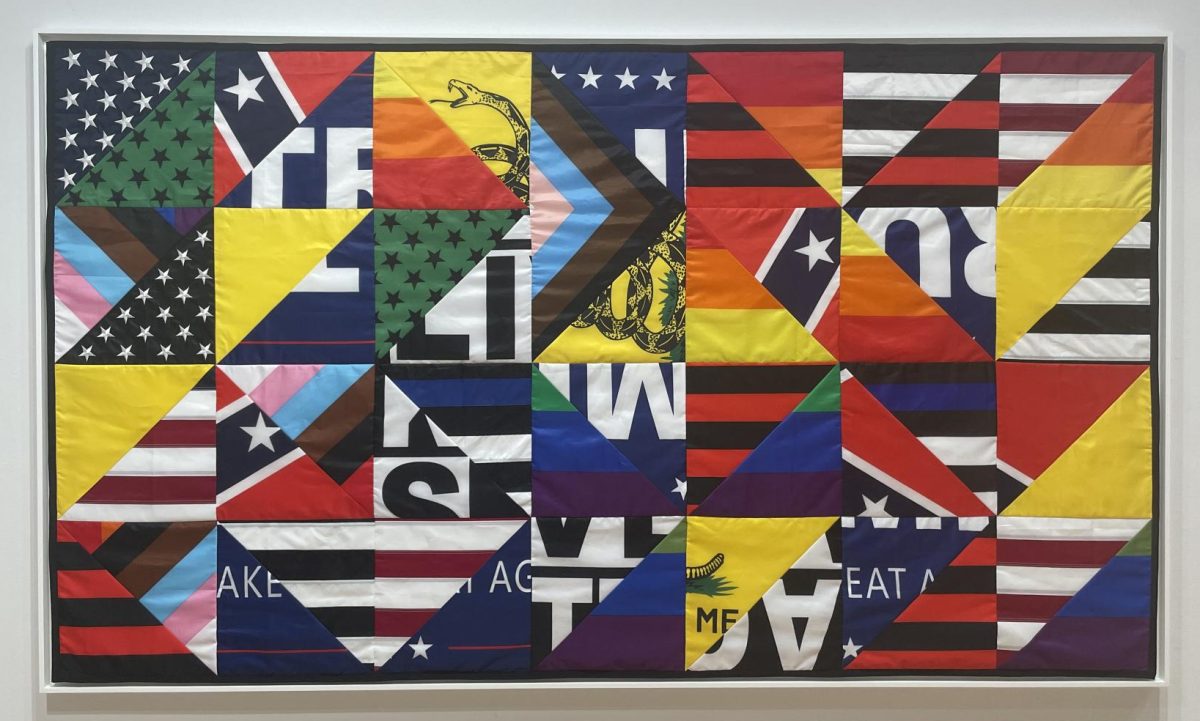

The piece that catches the eye immediately is titled “At the Twilight’s Last Gleaming?” The title is borrowed from the national anthem, but the question mark at the end subverts the audience’s understanding of the lyric, turning a patriotic phrase into a question and forcing the viewer to think critically about what the anthem and the correlated flag represents, and who it excludes.

The piece is an amalgamation of deconstructed political and identity-based flags that are highly relevant in the contemporary political landscape, patched together to create a new image. These include the American, Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ and pride flags, but also the Confederate, Make America Great Again and Gadsden (“Don’t tread on me”) flags. He took the symbols apart and pieced them together into a flag that is fragmented, contradictory and full of tension.

The piece is beautiful, while also telling a story of America’s political tension, and asking the question of who is and is not represented by the American flag, and if one single flag could accurately represent the United States and its diverse identities. The beauty of Thomas’ work lies in using symbols that the American public is deeply familiar with and forcing the viewer to critically analyze their meaning in a different way.

Throughout the exhibit, he asks these questions and more of the audience, particularly through the lens of altering their perspective both physically and figuratively. “He’s always thinking about how altering perspectives can alter perception; how it can change people,” Newman said.

In one piece, Thomas even uses a lenticular print, which requires the viewer to physically move their body to see the different messages in the piece.

He also uses UV print of reflected vinyl, the same material used in street signs, which requires light to see the entire piece. The exhibit encourages the audience to use their phone flash to reveal the concealed parts of the piece, and the material allows Thomas to present two distinct scenes.

Thomas was trained as a photographer. “To me, photographs are not documents, but really, storytelling tools,” Thomas said.

Photographs are a vital part of his artistic inspiration. “Photographs shoot us forward or backwards into space and time, because what’s in the frame of the camera is important, but what’s outside the frame of the camera is more important,” Thomas continued.

Speaking about his work with photographs and UV print, he said, “I’m interested in how what we choose to shine light on affects what’s visible—that’s extremely relevant when we think about historical images.”

Thomas explained that remembrance isn’t passive; we must be intentional about not allowing histories to be forgotten. “We can’t celebrate the present if we can’t acknowledge where we came from. So much of the show is to me about the perseverance and history of the American spirit.”