By: Delila Cruz ’28

Returning to Asheville the winter break of my freshman year was not the homecoming I thought it would be.

Hurricane Helene hit in September 2024, right at the beginning of my first semester of college. After seeing the content that was swirling around online, I dreaded the idea of going home. I couldn’t bear the thought of seeing one of my favorite places so disfigured. Indeed, parts of that December were as just jarring as I expected it to be. The city looked different, and I felt guilty for not returning to my family when I had the opportunity in October.

However, Helene brought me something unexpected: reassurance. Yes, things looked different, but I realized that the bones of Asheville were still the same. A common refrain you’ll hear around downtown is “Keep Asheville Weird,” and it’s true. Asheville is weird! The city is quirky looking, to say the least, and it’s the only place I know where people from such wildly different backgrounds can coexist so harmoniously.

Over that winter break, I listened to my parents’ stories of how various parts of the community united to support one another while waiting to receive outside help. One year later, I view the remaining wreckage as battle scars; they are the markings of a community that emerged from its trials stronger and prouder than ever.

If Asheville’s “weirdness” means that the people there will always rally around each other, then I hope the city continues to build back weirder.

By: Patrick Plaehn ‘28

Since Hurricane Helene, North Carolina has received 3.6 billion dollars from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. However, thousands of citizens are still waiting for reimbursement on their recovery expenses, and for many, these funds have come too late, with local Western North Carolina businesses continuing to close every day due to complications from hurricane Helene.

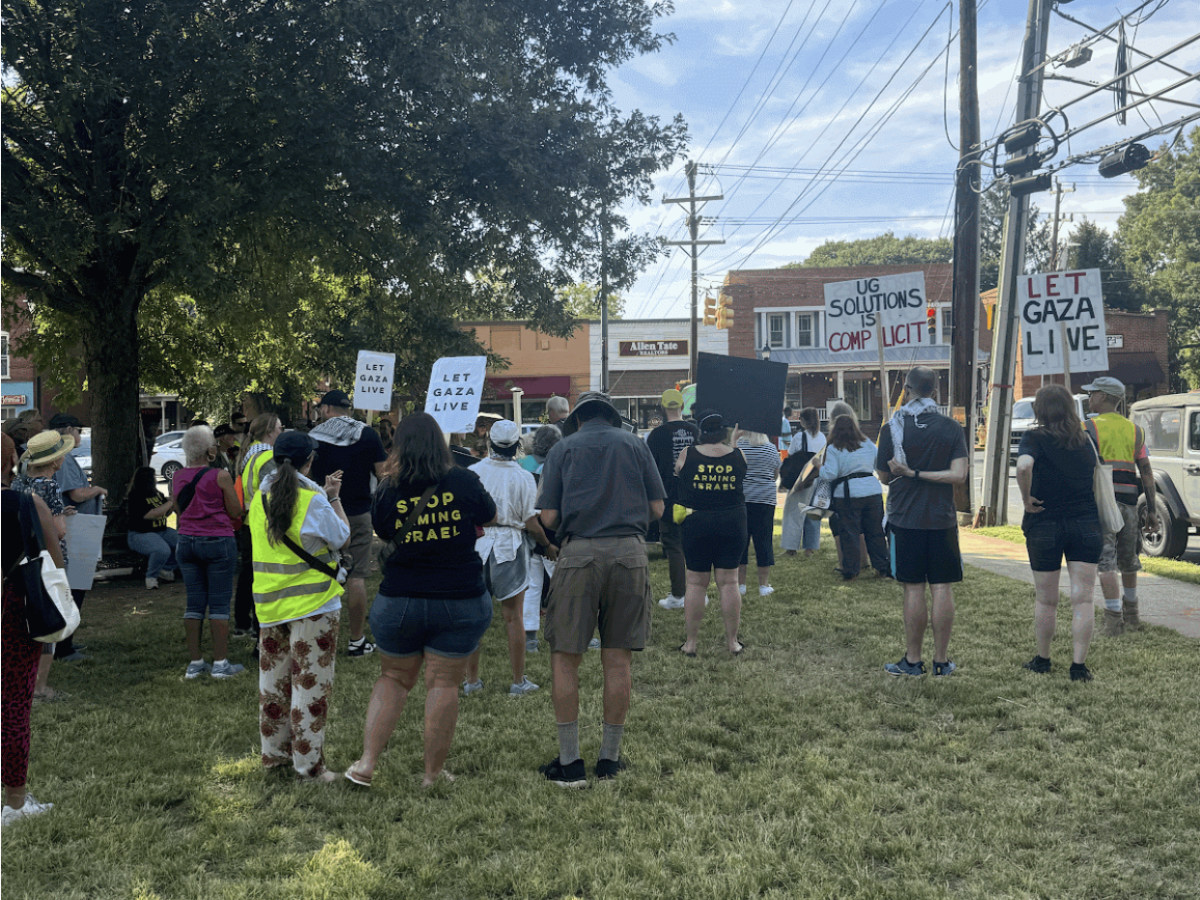

Keep in mind, the same day that Helene hit, the Biden administration approved 8.7 billion dollars in aid money to Israel to fund a war that a United Nations commission has now defined as a genocide. A few months later, the Trump administration slashed FEMA funding by 10 billion, and our president has threatened to withhold FEMA funding from states who are not complying with his immigration agenda, a move declared unconstitutional by a federal court in Rhode Island.

The Government Accountability Office has also reported that the administration has illegally withheld congressionally approved funding for FEMA programs several times in 2025. Our government has claimed that there is not enough money; they claimed they can’t save the livelihoods of millions of people living in the notoriously impoverished region of southern Appalachia, but we know that that is a lie; they just don’t want to.

Congressional committee leaders have introduced a bipartisan bill to restructure FEMA as an independent, cabinet-level agency, which may or may not help with these issues, but the underlying problem is the lack of money being allocated to those who need it most. We need a robust emergency response program for this new climate reality.

By: Mary Holmes ‘26

During the summer of 2024, I spent time researching (and playing) in Wilson Creek, a river in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. It was a beautiful place full of unique spots to swim, hike, fish, picnic, and more. I was eager to return after my semester abroad in the Fall, but the landfall of Hurricane Helene in the first month of my travels left me nervous about how the region had fared.

The environmental changes to Wilson Creek were insurmountable, but what struck me after dozens of visits this summer was the seemingly indefinite closure of many of the recreational segments of the river. Prior to Helene, I often encountered young families enjoying the area’s scenery—the majority of whom were people of color.

One year later, many of the more popular recreational sites were strictly closed, and those that weren’t had been washed out by Helene’s flooding. In terms of recreational visitors, Wilson Creek was more desolate than I had ever seen.

In a time when the most protected outdoor spaces are often financially or physically inaccessible to some groups, it is necessary to recognize the diminishing impact of climate change-induced natural disasters on the availability of local recreational nature.

By: Colin Decker ‘27

Everything as it once had been save faded and weathered. – Cormac McCarthy, “The Road”

Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road,” follows a father and son traversing a post-apocalyptic continent, fighting the impending sorrow of the darkness. Their only hope is a moniker: “Carry the fire.”

The apocalypse has become a literary genre all on its own. Authors can’t wait to paint literary portraits of the end times, and we can’t wait to read them.

I didn’t read about the apocalypse in a book. I read it in the downed trees by the road as I drove home. I read it in gutted houses with mildewing belongings piled on their lawns. I read it in the lamentation of my mother’s voice when she told me, “Some people literally have nothing.”

I read it in piles of donations stacked in my church’s sanctuary. I read it in news stories that named those washed away in the flooding. I read it on every street caked with mud, and on the face of every volunteer who helped people try to salvage normalcy.

Now, I read something else. The aftereffects remain, but are relegated to subtext. A more hopeful message bursts off the page: carry the fire together, and we can rebuild.

“So are you?”

“What, carrying the fire?”

“Yes.”

“Yeah. We are.” – “The Road.”

By: Abigail Przynosch ’27

I considered the mountain ridges of my hometown indestructible until a year ago, when Hurricane Helene tried to drown western North Carolina. The morning after the storm hit Asheville, I was flooded with news of missing person reports, demolished houses, and submerged streets. Not expecting this damage, I frantically tried to call my family and friends to ensure their safety, but was unable to reach anyone for three days.

Two hours away at Davidson, I felt disconnected and helpless about what was happening at home. After checking on other students from western NC, I realized everyone shared a similar sentiment: we wanted to help, but didn’t know how. At that moment, I realized the distance gave me two communities, and I could help connect the strength of Davidson back home.

Students, staff, and community members quickly reached out to support a campus fundraiser just a week after Helene. My peers donated art, played live music, provided food and equipment, and collected supplies as if helping their own loved ones. The Davidson community raised over $5,500 for NC Hurricane Helene relief, and more than ever, I felt the deepest sense of belonging I have experienced at this school.

When my mom admitted our family was running low on food, I thought of my Davidson friends packing meals to be shipped. When I returned home for Fall Break and saw neighbors carrying creek water to flush their toilets, I thought of the Davidson student who flew in jugs of fresh water. When I saw images of homes washed away in the floods, I thought of my peers who had researched and cataloged landslides in the area. A year after Helene, I’m reminded of the selfless individuals I attend Davidson alongside, and that “mountain strong” now belongs to more than just my hometown.

By: Brad Johnson

Friday morning of Helene was deeply strange for me. I was getting lots of interview requests and my phone was constantly ringing while it remained dark as night outside through the morning. In those interviews, all I could talk about was what might be happening because communication from communities in the Blue Ridge was so limited. I felt like I needed to constantly scroll every social media platform to keep ahead of the people who were interviewing me. A few photos and videos were leaking out of the Blue Ridge and they confirmed many of my worst fears. Water was everywhere, and it was deep. In the days after Helene, I worked to bring supplies to western North Carolina and help out individual landowners. As I drove around, I was struck by how powerful and broad the floods had been and how much destruction there was in the river corridors. While I’ve studied both landslides and rivers throughout my career, I’ve actually spent more of my time working on rivers than landslides. How had I missed the potential impact of flooding during a hurricane in the Blue Ridge? Why wasn’t I as focused on warning people about the impact flooding would have on valley bottoms?

Nature is remarkably resilient – many of the river corridors that looked awful in the weeks after Helene suddenly look better with a growing season under their belts. Human structures are not particularly resilient and it is a simple lesson to learn to stay out of the way of floodwaters. If you move structures back and away from flooding, you can basically watch the flood happen and be back to normal within weeks when bridges are rebuilt and roads are cleared of debris.