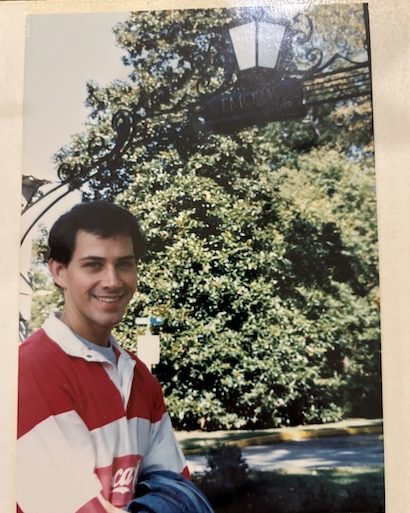

Imagine you’re a college basketball fan in 2007. After a dazzling freshman year at Davidson, Stephen Curry ‘10 captures the national spotlight during his sophomore season, becoming a household name en route to the Elite Eight. The problem? The team he leads isn’t Davidson. It’s Duke. Why? He accepted a million-dollar check to transfer to a better program.

Welcome to college athletics in 2025. The transfer portal and NIL––a recent rule that allows players to profit off their name, image and likeness but has essentially morphed into schools paying players—have flipped athletics on its head. And Davidson is no stranger to the struggles in this new environment: our A-10 All-Conference First Team forward Reed Bailey and Davidson’s third-leading scorer Bobby Durkin have both left for greener pastures at Indiana University Bloomington and the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, respectively. Football has been impacted by the portal as well: once former Head Coach Scott Abell left for Rice University, and over fifteen players chose to enter the portal. If you’re a fan of any major collegiate football or basketball team, your squad is often unrecognizable, made up of players from a bunch of different teams. And just when you learn their names, the revolving door of transfers brings in a completely new roster.

What makes this new era even harder to swallow is the amount of NIL money thrown at athletes younger than many reading this article. The University of Tennessee’s quarterback transferred because they wouldn’t pay him $4 million dollars to stay. Ohio State University’s 2025 College Football Playoff championship team was led by a transfer quarterback who captained a $20 million dollar roster. Top players often collect more than $100k a year, and the best of the best make seven figures. College sports are no longer what my generation grew up with, and they’re certainly a far cry from what my father has loved since his childhood. The romanticized notion of amateurism and players committing to one school their whole college career are relics of the past, and from a fan’s perspective, that can be weird. From a Davidson student’s perspective, losing the core of our basketball team for next season really sucks.

But that doesn’t mean what’s happening is bad or wrong. Rather, these changes prevent collegiate athletics from continuing to take advantage of student-athletes, as it had been doing for over sixty years.

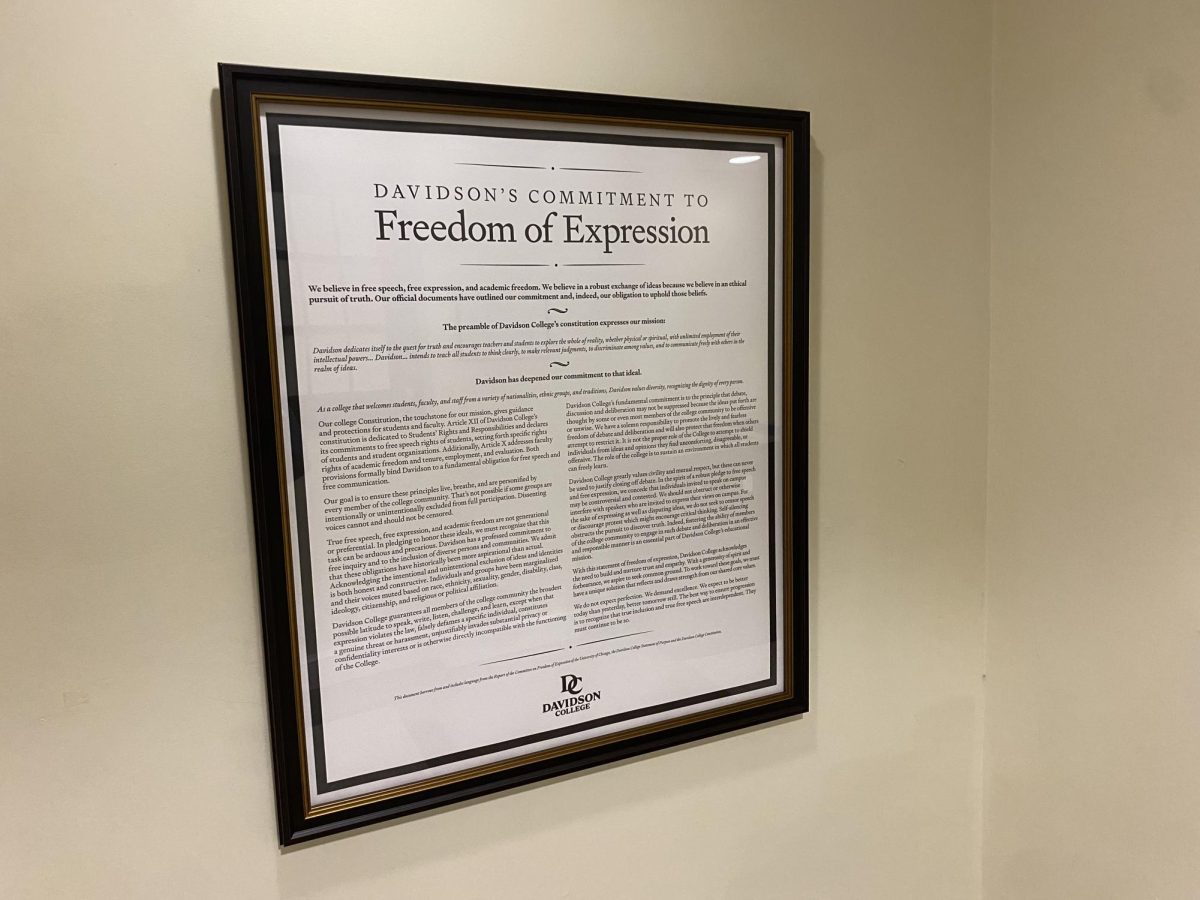

Some schools generate over $100 million in revenue from their athletic programs, not to mention the incalculable benefit from application spikes and general brand recognition. However, student-athletes have never had the opportunity to profit from a system that relies entirely on their work. Yes, some scholarships cover the cost of college education, but that doesn’t make up for those denied the additional revenue their fame entitles them to. NIL became legal just four years ago, allowing student-athletes to profit off their fame during the most high-profile years of their lives. Within the next few months, universities will be allowed to pay athletes directly. The current situation isn’t a travesty bringing about the death of amateurism—it’s people becoming able to fairly profit off their abilities and fame instead of athletic departments concentrating all the revenue. We may not like seeing a twenty-year-old make more annually than 99.9% of America, but so what? If the market deems they’re worth that much, our opinion on whether it’s right or wrong doesn’t matter. Furthermore, everyone knows someone like Cooper Flagg will make millions regardless of NIL, but for elite volleyball players at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln or star softball players at the University of Oklahoma-Norman, their four years in college are when their fame and earning potential will be at its highest.

The current wild-west style of transferring should not and likely will not continue indefinitely, what with players transferring multiple times in a span of three months. But even with regulations in place, many think the new dawn of collegiate athletics will leave Davidson unable to compete with larger schools. And, frankly, this sucks.

Ten years ago, with the right mix of roster continuity, coaching and luck, a small school could legitimately contend with the Alabamas and Dukes of the world—look at Loyola University Chicago in basketball and Boise State University in football. Now, there are maybe only thirty football and fifty basketball teams that could ever win the national championship. Cinderellas will absolutely still exist, but we may have to temper our expectations on how long they dance. This isn’t the players’ fault—Reed Bailey isn’t transferring to destroy the mold of collegiate athletics, he’s transferring to better provide for himself and his family and, from his perspective, give himself a better opportunity to reach the NBA. And it’s not the fault of the NCAA or any college administration either—they shouldn’t sacrifice integrity just so small schools can seriously compete. I want Davidson to remain nationally-relevant athletically (and I think we will), but larger schools dominating is where this model was always heading.

Collegiate athletics remain imperfect, but

limiting what student-athletes can earn or restricting player movement to preserve a decades-old system is unjustifiable. The new system may take some to adjust to, but it is no one’s fault—it’s just how the system has evolved. And for all the hysteria over multi-million dollar NIL sagas and players enrolling at five universities over four seasons, there remains a vast majority of student-athletes who stay loyal. As much as things are changing, the heart of collegiate sports will remain, and who knows? Maybe Stephen Curry wouldn’t have transferred after all.

Asa McCaleb ‘28 is a history and economics double major from Dallas, TX and can be reached for comment at [email protected].