Throughout my four years at Davidson College, I have been closely involved with Davidson’s public history efforts. Since co-founding the Historical Campus Tour on colonialism, enslavement and white supremacy in 2023, I have gained an intimate understanding of the College’s patterns of narrative control. On paper, the College is taking the ethical and progressive steps toward equity and racial justice: constructing a memorial to the enslaved people who built Davidson’s campus, hiring new Africana Studies professors and turning Beaver Dam Plantation into an educational center. However, there is a logic guiding the decisions about reparative actions: these measures make no structural changes to the College’s operations, and no money leaves the College’s ecosystem.

Throughout my four years at Davidson College, I have been closely involved with Davidson’s public history efforts. Since co-founding the Historical Campus Tour on colonialism, enslavement and white supremacy in 2023, I have gained an intimate understanding of the College’s patterns of narrative control. On paper, the College is taking the ethical and progressive steps toward equity and racial justice: constructing a memorial to the enslaved people who built Davidson’s campus, hiring new Africana Studies professors and turning Beaver Dam Plantation into an educational center. However, there is a logic guiding the decisions about reparative actions: these measures make no structural changes to the College’s operations, and no money leaves the College’s ecosystem.

In imagining pathways to justice and repair, I continuously look to Panashe Chigumadzi, an Africana historian and journalist who reminds us of what reparations require. In her 2023 essay “With What Are You Apologizing?” Chigumadzi grounds reparative action in the reality that “transatlantic slavery is the material and metaphysical womb of the modern world.” Because everything in existence was built and has been sustained by colonialism and slavery, it follows that any redress for harm would be empty without a transformation of those very structures and systems, an end to this modern world. Chigumadzi fixes her analysis in the African philosophy of Ubuntu, a framework that demands costly forgiveness. “You cannot receive forgiveness without giving something up as an act of your contrition,” she writes. If slavery is the womb that birthed this college, its repair must be costly, material, and transformative. Over the past few years, however, I have witnessed the Davidson College administration attempt to control its institutional narrative in order to maintain its authority, wealth and whiteness.

Davidson College was founded in 1837 through the ethnic cleansing of the Catawba Nation and with wealth generated from the subjugation and enslavement of Africans. The College has been the most forthcoming about its history of slavery, materially and metaphorically represented in the campus bricks constructed by enslaved people. However, in emphasizing this history only in the College’s origins, this narrative displaces how enslavement and white supremacy have sustained the College through its entirety. There is no better example of this than the impact of Maxwell Chambers, an enslaver and participant in the transtlantic slave trade, whose wealth was necessary for the College to remain open during the Civil War and to begin to expand its endowment.

I arrived on campus in 2021 with some of this historical knowledge. Like many students, I had watched Carol Quillen’s apology video, read through the Commission’s report, and was appreciative of Davidson’s transparency—not every university, let alone a small liberal arts college, takes ownership of its violent histories. It was not until I moved into Davidson’s dorms that I realized how much hunting was required to find this history. The Disorienting Davidson Tour, created by HD Mellin ‘20 and Tian Yi ‘18, in addition to James B. Duke Professor of Africana Studies Dr. Hilary Green’s course “Race and Campus History,” would eventually ground my knowledge in Davidson’s entanglement with racial capitalism and white supremacy—a relationship that connects together centuries of exploitation and expropriation.

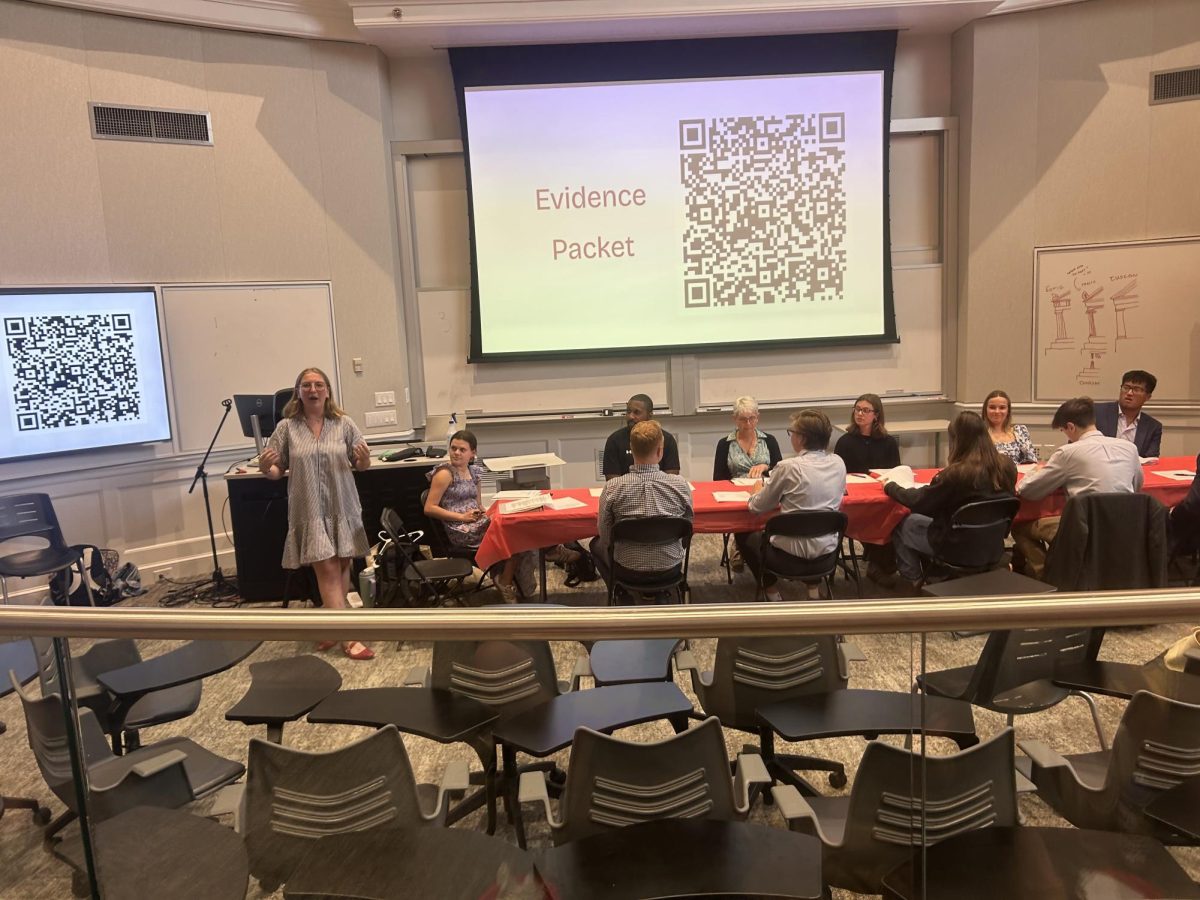

During the summer of 2023, Lauren Collver ‘25 and I founded and designed the Davidson College Historical Campus Tour, a project intended to spread knowledge about our campus history and tie Davidson’s past to its contemporary operations. Soon after planning began, we were approached by Associate Chaplain Daniel Heath, whose support from the Davidson Forum allowed for the tour to develop and for tour guides to be paid. Nevertheless, the tour program has remained almost completely student-run. The guided walking tour takes participants from the decimation of the Catawba Nation and forced labor of enslaved Africans to racial violence of the 20th and 21st centuries, such as racialized halftime performances at football shows that featured Black children, or the Lost Cause nostalgia that remained alive on campus for over 100 years after the Civil War. White supremacy did not end with the abolition of slavery, with the Civil War or with racial integration. It has merely been replicated and reproduced.

After sending the first draft of the tour script to President Doug Hicks’ ‘90 office in October 2023, and after every college vice president took a pilot tour, we heard nothing from the administration for months—not until the day before our first public tour in February of 2024. While some of their edits provided additional context, the administration’s comments were largely disapproving. They made clear a desire to maintain authority over knowledge production, frame racial violence as a symptom of a bygone era and obscure the College’s relationship with white supremacy. Over the past two years, I have only been confirmed in this suspicion.

The administration initially claimed that our scholarship was difficult to “fact-check,” as we cite secondary sources that discuss colonialism and enslavement on campus, sources they deemed “interpretative.” This criticism was only directed toward student and faculty research, such as HD Mellin’s student thesis Beneath the Bricks. The administration found no issue with our citations of non-peer-reviewed reports from the institution itself. By drawing this double standard, the Davidson administration proved the limits of its own institutional reckoning: knowledge is only valid if the administration maintains the authority to make that validation.

In their edits, the administration also critiqued the tour’s lack of recognition of “the college’s” initiatives. The script’s discussion of Dr. Green’s report on Chambers was not enough—they wanted it to be clear that “the college” commissioned the report, as if Dr. Green or even we as students were in fact not part of “the college.” Beyond defining who can and cannot claim to be part of “the college,” the very assumption that the administration should be applauded at all comes into question. Why should we celebrate the administration for raising the minimum pay to $13.50 only in October of 2021, when generations of families have been staff for Davidson College since emancipation? Why should we deem the College progressive for hiring four more Africana Studies faculty in 2023 when demands for an Africana Studies department are rooted in the 1980s? Why did histories of racial violence and exploitation only become important to the institution in 2017 when the Commission on Race and Slavery was founded? Did the College only realize that mass murder, enslavement and exploitation were wrong within the past decade? The answer here is not that Davidson’s past actions were contradictory to its mission, or that the College has had a few bad actors. In reality, Davidson’s actions over time have remained in line with the College’s origins of colonialism and enslavement. Institutions make choices that seem progressive when there is no other option, when it’s too difficult to keep the skeletons in the closet, and when transparency is both financially beneficial and allows Davidson to keep pace with competitor institutions that are all reckoning together.

In the administration’s request for more praise in the tour script and their attempt to balance every negative harm with a positive step, they affirmed a belief that the College should be commended for their work without making sacrifices to their land or wealth. A brief glance at the “Post-Commission Initiatives and Progress” page on Davidson’s website plainly shows that no money has left the College and that all steps toward equity and racial justice have only been in service of the people of Davidson College. For example, initiatives to hire new faculty members or increase diversity, equity and inclusivity programming—while important for creating an inclusive campus culture—do not redistribute any money away from College itself. These steps work to also increase the College’s prestige without forcing the institution to make any structural changes. The upcoming monument “With These Hands: A Memorial to the Enslaved and Exploited” was estimated to cost $4 million, money that could have been put directly into the hands of descendant community members, but the construction of a monument is seen as a necessary measure for institutions of higher education. This step is costly, but is it forgiveness? A monument is not necessarily in service of members of Davidson’s descendant community or even members of West Davidson. It is an art piece that will sit on Davidson’s land, for its students, faculty and staff to solemnly digest and reflect without promising meaningful repair. If justice is assumed to equal the severity of harm, the College makes clear their belief that awareness through art and education is equal to that of theft, bondage and death.

Simultaneous to Davidson’s institutional initiatives that claim pillars of equity and justice, the administration’s narrative control has attempted to displace contemporary racial violence. In adapting our in-person guided walking tour to a virtual interface, the language of our initial script was heavily sanitized. Though a virtual tour required a shorter and less dense script, all decisions of what to cut and what to keep hold political weight. The edits from the virtual script erased most modern instances of racial violence, removing history after the 1980s unless it had a positive spin. For example, the editors replaced information about KKK and Confederate imagery in Kappa Alpha spaces with an anecdote about Mike Malloy ‘70, a story that applauds a Davidson fraternity for their solidarity with an African American student. Though an important act of resistance, this was a singular and rare moment of white student support within the backdrop of decades of white supremacist activity within fraternity spaces.

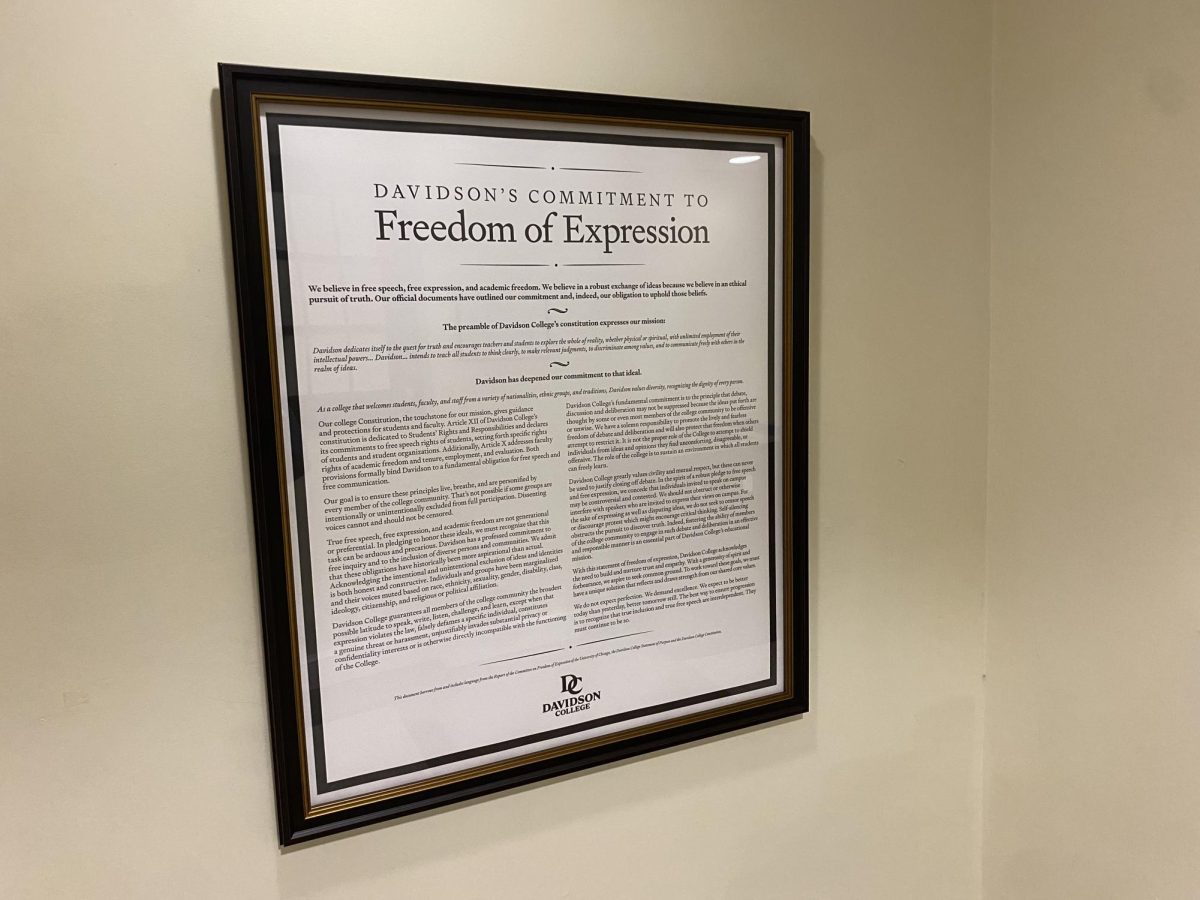

The subtitle of the tour itself was also changed from “Davidson’s Legacy of Colonialism, Slavery, and White Supremacy” to “Race, Slavery, and Segregation.” In changing the title, the College disconnects slavery from contemporary manifestations of white supremacy. “Segregation” specifically denotes a Jim Crow era squarely in the past. This obfuscation is present across the administration’s operations. Despite staff from the Office of Admission & Financial Aid claiming appreciation for the tour and requesting to collaborate, they required us to change the language on our flyer if we wanted to promote the program to prospective students. One admission officer wrote to us in an email, “while we want to be as transparent as possible, we simply can’t have the triggering words ‘colonialism, slavery, and white supremacy’ cycling through our lobby.”

It has been almost two years since we began designing this tour, and longer since I started to observe Davidson’s work to repair. To quote Chigumadzi, I ask, “with what is Davidson apologizing?” Chigumadzi reminds us that forgiveness must be material, yet Davidson’s initiatives only work to grow the College’s financial, social, and political investments. The administration holds a tight grip on its institutional narrative because they know it is cheaper to obscure the College’s ongoing relationship with white supremacy than sacrifice any of their land or wealth. They deeply understand that, once you start pulling the strings of history, the alleged values of the institution become increasingly hollow. What’s left is the web of exploitation and dispossession that binds the College together. You realize that the Honor Council was founded the same year that the College began talks of racial integration. You learn that the College laundry service, which only ended in 2015, was not created for student convenience but as a way to control entrepreneurship of the town’s Black laundresses and delivery men. You draw lines between the beautification of the College’s greenway on Griffith Street to the displacement of Black residents. You come to the conclusion that promises of racial justice are not just empty but smoke and mirrors intended to keep you disillusioned and docile, to convince you that Davidson is doing the most they possibly can—that is, they are doing everything possible within the limits that maintain Davidson’s wealth and whiteness.

With what is Davidson apologizing? Can their apology ever be meaningful if the structure and logics of the institution remain the same? Repair requires a radical reimagination of what exists and what can be. An educational institution like Davidson does not have to prioritize the accumulation of capital. It does not have to serve only its students, faculty, and staff. It does not have to only pay employees the minimum wage to live. What would it look like for Davidson to redistribute wealth and land to the communities it has harmed without any strings attached? To open its borders in alignment with the belief that every person deserves education? To prioritize care and liberation as core values instead of competition and prestige?

I write this article not to be ungrateful or accusatory. The administration’s decisions mirror the strategies of every institution of higher education, which simultaneously builds and has been built by systems of oppression. To echo Chigumadzi, justice demands that we ask the impossible of the institution and the impossible of ourselves. True justice and repair mean the end of the modern world, and we should not accept anything less.

Anaya Patel ‘25 is an Africana studies and anthropology double major from San Antonio, TX and can be reached for comment at [email protected].