Dr. Tova Benjamin and Dr. Yaakov Lipsker arrived at Davidson in the fall of 2024. Benjamin, assistant professor of history and Russian Studies, and Lipsker, assistant professor of practice in humanities and Jewish Studies, are Davidson’s first long-term Jewish Studies hires.

Benjamin studied modern Jewish history, late imperial Russian and early Soviet history while completing her PhD at New York University (NYU). While looking for jobs, she came across an advertisement from Davidson that stood out.

“It is pretty rare to see a job for a Russianist who specializes in Jewish history,” Benjamin said. “I’m not sure I have known about a job that was specifically looking for someone with that designation so I found that really interesting and exciting to get to start a position that was asking for both of my specialties.”

A more broadly trained historian, Lipsker came to Davidson from the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), where he received a PhD in Modern Jewish History.

“What was special for me about being at JTS was that I was able to study with my advisor, who’s a specialist in East European Jewish history, but also to take courses at places like Columbia and NYU to ground myself in the broader context of my research field,” Lipsker said. “I was very happy with the opportunity to teach Jewish Studies broadly at a place like Davidson, where there’s been a kind of grassroots effort on the part of certain students in recent years to have some sort of Jewish Studies offerings comparable to other schools.”

Benjamin and Lipsker both think a lot about the how and why that underlines their teaching at the College and what it means to be historians in the current moment.

“When you’re working on topics or subjects that are not about the U.S., there’s always this expectation that you’re going to explain why it’s interesting to people,” Benjamin said. “[…] I think it is a really good thing if I think about why this should be interesting to me, or why [people should] care about this. It forces me to think about how the subjects I study are actually attached to much bigger questions.”

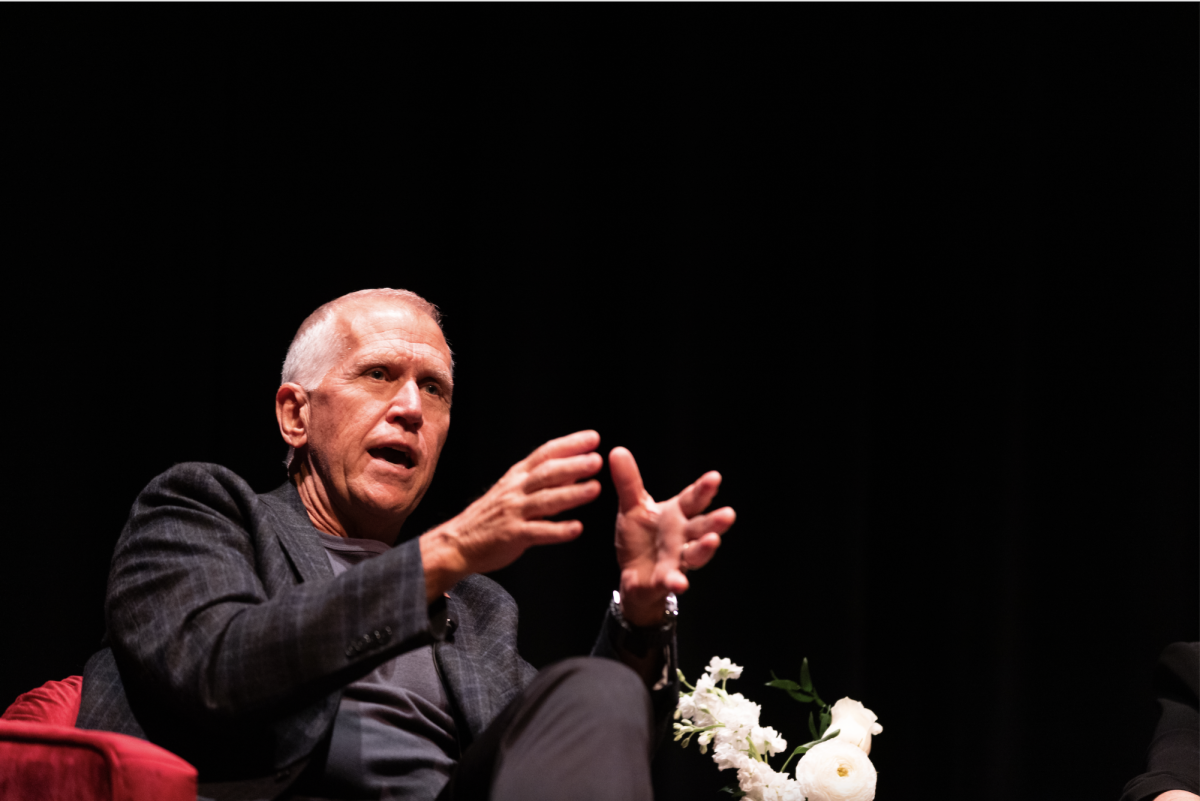

In terms of his approach to teaching, Lipsker sees it as a liberatory act.

“History, and Jewish history, for me, […] helps unshackle people from the concepts and the normative ideas that really constrain many people’s thinking,” Lipsker said.

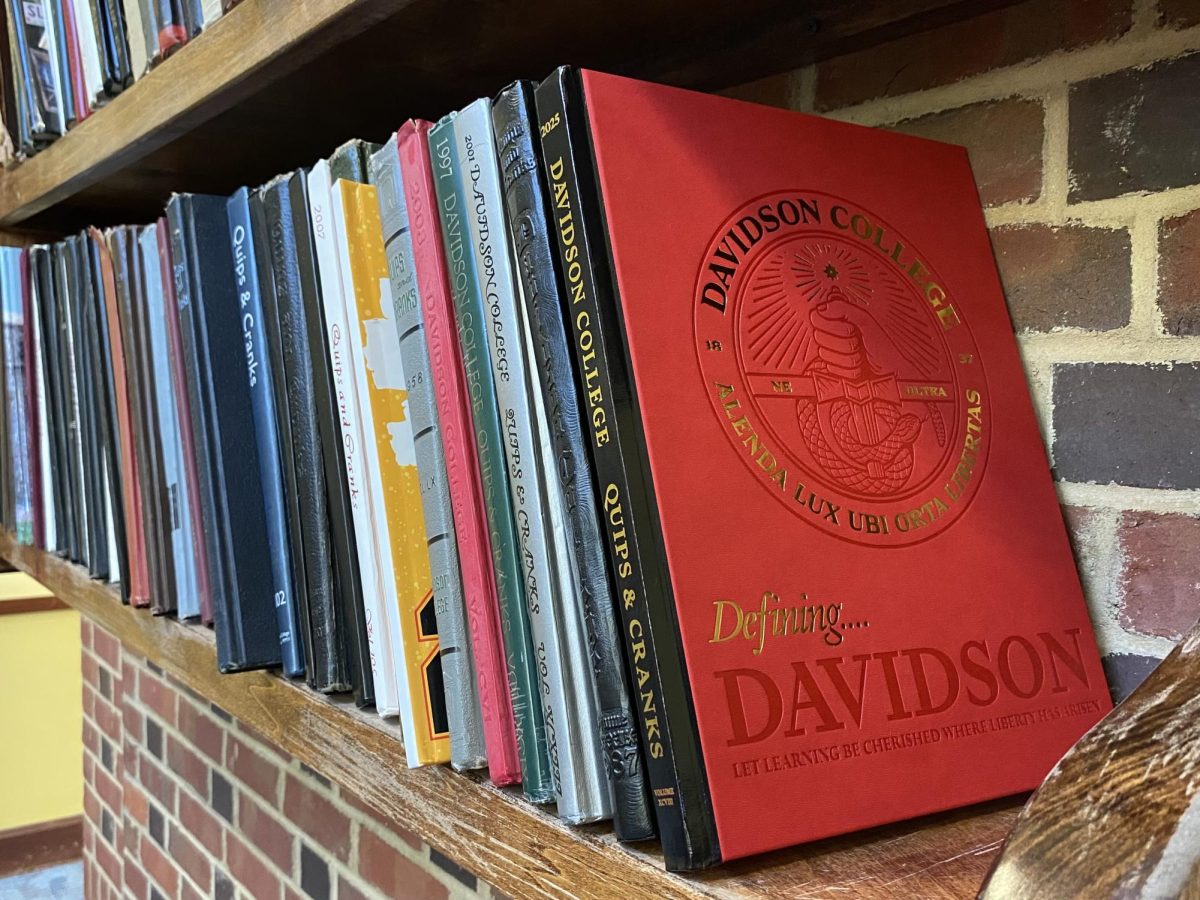

A long time coming.

Students have been pushing the Davidson administration on and off for years to hire Jewish Studies professors and create the foundation for what could eventually become a Jewish Studies major or minor. Professors in German Studies, Religious Studies and a few other departments have integrated elements of Jewish Studies into their courses in previous years. Visiting professors have come and gone. So have Neo-Nazi students, changing faith requirements for faculty and a diversifying student body. Various departments thought about applying for a tenure track professor specializing in Jewish Studies but could not or did not make the move. Then Russia invaded Ukraine.

“When the full-scale invasion happened, I don’t remember the exact moment when I started to talk to Patricia Tilberg about it, but it was kind of this lightbulb moment, or maybe like a burning bulb that gradually lit up,” Chair & Professor of Russian Studies Dr. Amanda Ewington said.

Ewington, alongside Chair & James B. Duke Professor of History Dr. Patricia Tilburg, created Benjamin’s position, intentionally highlighting the need for expertise in Eastern European Borderlands.

“My former colleague put together this big workshop at Amherst College […] a year after the full scale invasion, bringing together Russian studies professors from small liberal arts colleges to talk about ‘What does it mean when we keep talking about decolonizing the curriculum in the context of the war in Ukraine?’ because the people who actually studied the region understood, and do understand, that this is a war of colonialism, this is an imperial war.”

Ewington had also been working for many years to

re-establish a tenure track line in Russian Studies.

“There are a lot of different things that needed to be done, and this was bringing it together in a way that felt organic,” Ewington said. “It didn’t feel forced like it felt more like that aha, moment like of course this is what needs to happen. It felt significant curricularly and frankly, just at that moment.”

So she got to work.

“Part of it was doing our homework and being able to show the dean [of faculty] this is a real thing, this is a major way that people are trained in this overlap of Russian imperial history, Ukraine, which was in the job ad, and Jewish history, which was in the job ad,” Ewington said.

And that is exactly how Benjamin was trained.

“I think since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in the field of Russian Studies people have been really rethinking the way they teach Russian history and thinking about the peripheries rather than the center and approaching the empire from its peripheries,” Benjamin said. “Seeing somebody conceptualize a position in Russian history that was being thought of from the peripheries rather than from the center communicated something about how the people here imagined Russian history to be taught. And that was exactly how I had been trained in it too.”

Jewish Studies at a Presbyterian college.

Davidson’s identity as a Presbyterian college remains largely out of mind in the day-to-day lives of many students and faculty. However, it is not quite out of sight. “The Christian Commitment of the Faculty,” a subsection of the College Bylaws, holds that faculty members must “live in harmony with the Statement of Purpose of the College.” Davidson’s Statement of Purpose, following the commonly refrained commitment of preparing students for lives of leadership and service, reads:

“The Christian tradition to which Davidson remains committed recognizes God as the source of all truth, and believes that Jesus Christ is the revelation of that God, a God bound by no church or creed. The loyalty of the college thus extends beyond the Christian community to the whole of humanity and necessarily includes openness to and respect for the world’s various religious traditions. Davidson dedicates itself to the quest for truth and encourages teachers and students to explore the whole of reality, whether physical or spiritual, with unlimited employment of their intellectual powers. At Davidson, faith and reason work together in mutual respect and benefit toward growth in learning, understanding, and wisdom.”

While today’s statement of purpose promotes inclusivity, that has not always been the case. Davidson did not offer tenure to non-Christian faculty until 1977. When asked about how the College’s affiliation with the Church guides hiring practices today, Dean of Faculty Dr. Shelley Rigger had this to say:

“If a job candidate or someone I’ve made an offer to wants to talk about the Statement of Purpose, the way that we talk about it is in terms of what being associated with a particular religious tradition allows us to do. We’re not asking people to hold a truth statement. We’re asking people to be able to be in a community where particular values are upheld. The virtue of the Reformed Tradition, the specific tradition that Davidson is part of, is that it is an open-minded tradition.”

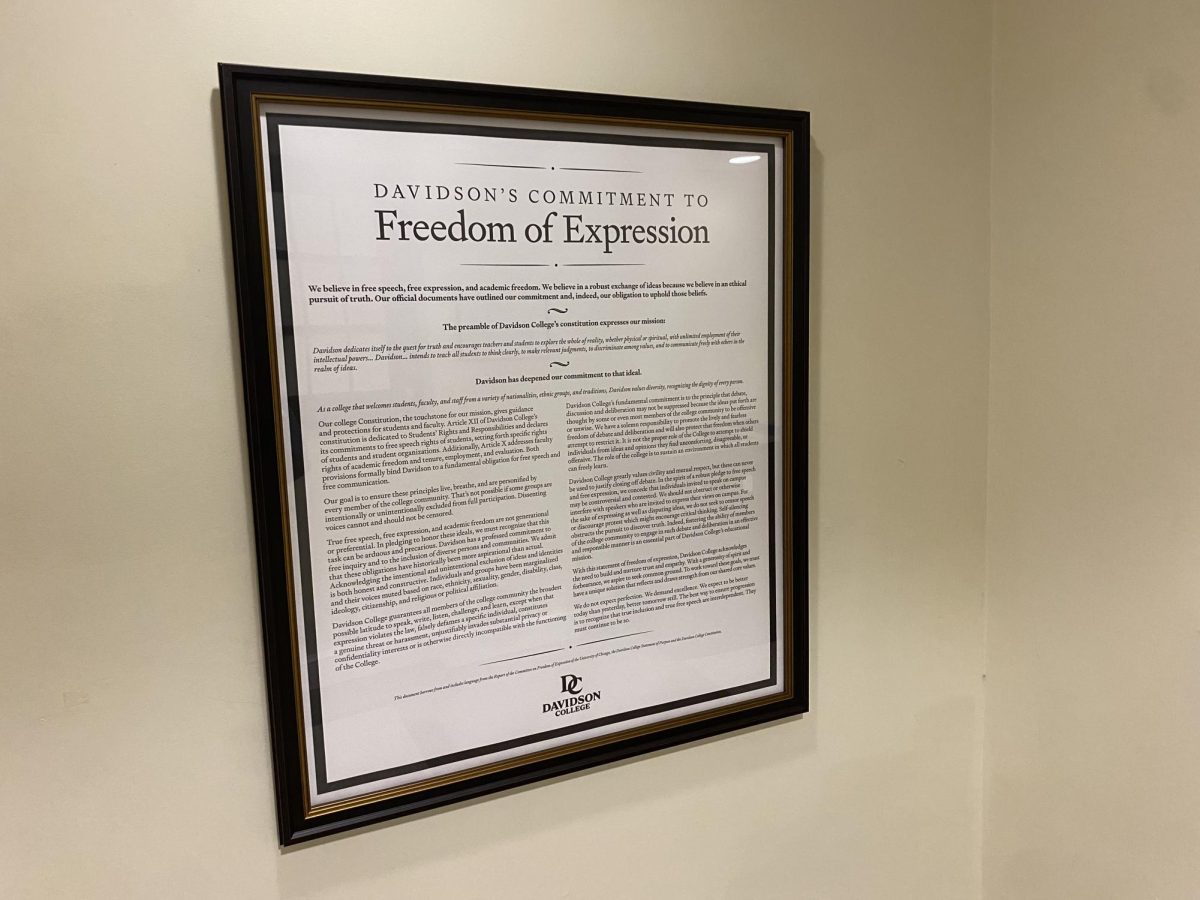

Neither Benjamin nor Lipsker said they felt an influence from the College’s religious affiliation at any point during either of their hiring processes. On the contrary, Benjamin saw what she described as a dedication to academic freedom at Davidson that made it stand out from other institutions.

“There’s a lot of ways where I think the institution is working very hard to try and preserve that commitment to academic freedom and also to preserve faculty autonomy,” Benjamin said. “I think those things are really important if we care about the education that students are getting, and if we care about the university as a place where they get to ask hard questions and hear hard answers.”

Now and into the future.

As Benjamin and Lipsker finish their first year of teaching at Davidson, Ewington highlighted the timing.

“I am grateful that we as a college showed a commitment a long time in the making, an overdue commitment,” Ewington said. “I feel a little corny, but I am so grateful for Dr. Benjamin’s presence and Dr. Lipsker being here right now. It feels like a much overdue fortuitous injection of people who know things.”

Rigger echoed Ewington’s gratitude.

“I feel incredibly lucky that we were able to hire two people who,between them, can really cover a very large span of what students are hoping to learn in the field of Jewish Studies.”

Benjamin and Lipsker have many ideas and plans for their future at Davidson, and appear clear-eyed in their place here.

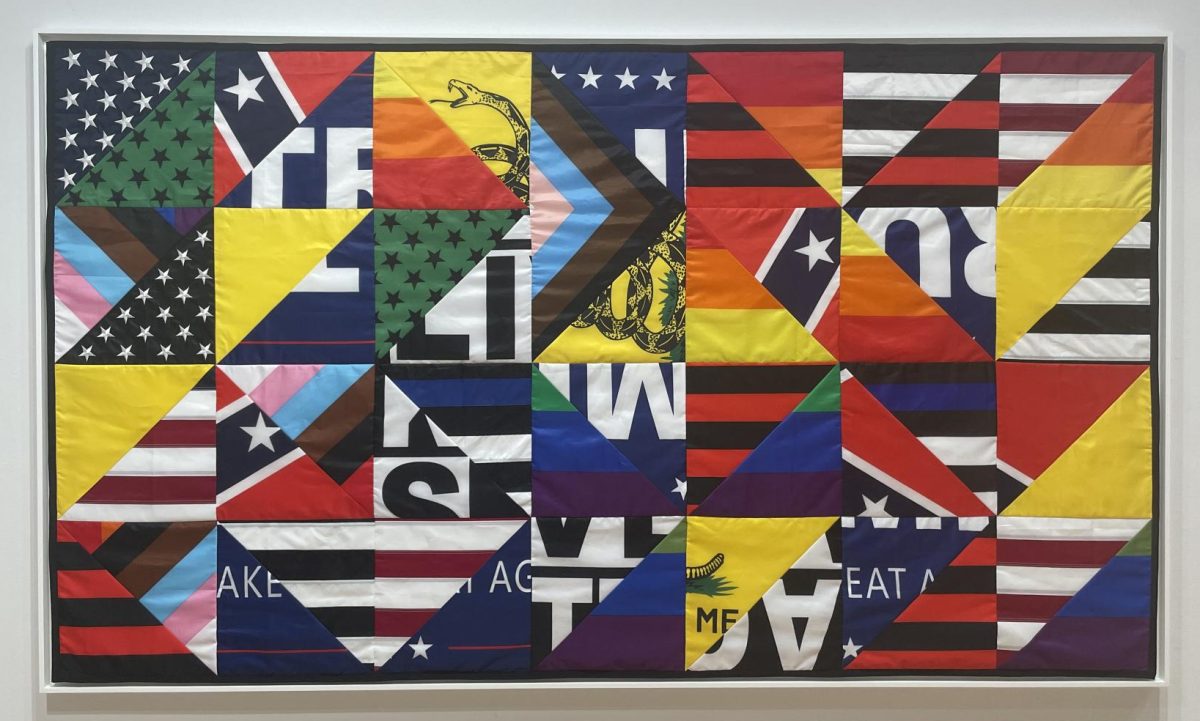

“I think history can be liberatory, not just for Jews obviously, but for anyone who is trying to have a more nuanced understanding of the Jewish past,” Lipsker said. “I think that is critical at a moment where the president of the United States is invoking Jewishness and Jewish safety or Jewish concerns as a way of boxing in what can and cannot be said, researched, thought about in a context of the university, which is precisely the place where those questions need to be thought about in a measured way. From that perspective, Jewish Studies and Jewish history is more important than ever.”

For a more detailed exploration of the history of Judaism and Jewish Studies at Davidson, visit https://digitalprojects.davidson.edu/jewishidentity/.