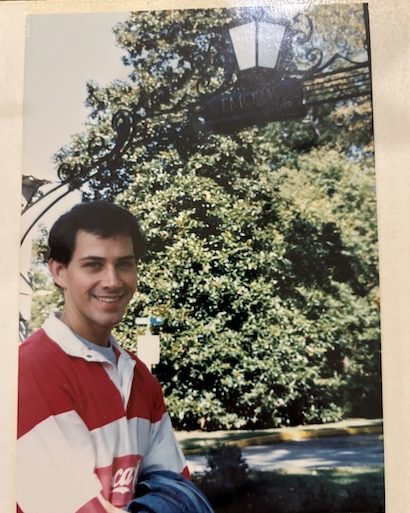

A young Randy Ingram in his days as a Davidson student. Photo courtesy of Randy Ingram.

The first thing you see upon entering Professor Randy Ingram’s (‘87) office is an almost ceiling high bookshelf. That bookshelf is populated by the accumulated material of a man who has dedicated his professional and personal life to studying and teaching the written word. The books range from multiple copies of Paradise Lost to contemporary material such as Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach. The books are all strewn about in the charmingly disorganized fashion that one would expect from a man who has taught English at Davidson since 1995, and who is teaching the last two classes of his lengthy career this semester.

One author featured prominently on Ingram’s bookshelf is Geoffrey Chaucer, which makes sense: as a first-generation college student from North Carolina’s Rockingham County, Dr. Ingram was first drawn to English while taking Davidson’s required survey of English literature. As he recalls: “I was making an A in chemistry and a C+ in English, but when I was outside of class I found myself constantly thinking about Chaucer, not chemistry.”

And thus began Dr. Ingram’s time in the Davidson College English Department. Davidson was, initially, a daunting place for him: “students wore shirts with logos that I didn’t recognize—I couldn’t tell if shirts had private school logos or clothing brand logos or what.”

To a small-town North Carolinian, Davidson, although itself a small North Carolina town, might as well have been “another planet” with its wealthy families and children of privilege brought up at private schools. He credits the late Professor Anthony Abbott, who eventually became his major advisor, with helping him find his place on campus. Upon discovering his passion for the written word, Ingram threw himself into nearly every activity that involved it. He was the chairman of the Literary Arts Committee on the Union Board, which involved reaching out to prominent literary figures and asking them to come to campus.

Literarily, Dr. Ingram was raised on the white, western-centric curriculum of the Davidson College English Department at the time, something typical of most English departments in the nation then: a sweeping grand narrative that framed literary history as shaped by and for white men. He says that he and other students at the time were “conscious of the voices that were excluded from that canon.”

His chairmanship of the Literary Arts Committee was one area in which he tried to counteract that: he fondly remembers that “Gloria Naylor declined my invitation by letter!”

To this day, even though Ingram’s specialization is in the predominantly white and male field of 15th-18th century literature, he includes diverse voices in his syllabi (for example, last year’s “Literary Satans” included a remarkably diverse range of authors, from John Milton to Malcolm X to Sharon Olds), and he strives to create a classroom environment in which students from diverse backgrounds feel like they can partake in conversations that they were excluded from, historically.

Annelise Hawgood ‘27 says his charm is rooted in the equal conviction with which he teaches “conventionally canonical material” and its non-canonical counterpart.

In speaking with Dr. Ingram, one immediately understands that the most rewarding aspect of his job is engaging with students, who he treats not as students, but as peers.

“He abolished hierarchy in the classroom without saying a word,” Hawgood said.

Indeed, if there is a secret, almost ineffable quality that undergirds the tremendous pedagogical success that Ingram has had (such as receiving the Hunter-Hamilton Love of Teaching Award in 2007), it is the glowingly obvious interest and respect with which he treats his students’ lives and perspectives.

Despite students being significantly less credentialed, “Dr. Ingram constantly encourages students to share their thoughts, and often values those student perspectives more than his own” Maren Lawee ’26 said.

Eight years after Ingram graduated, Davidson needed a part-time professor to teach a course on John Milton. Ingram, whose dissertation was on Shakespeare, cobbled together an application which established sufficient Miltonian bonafides. He was hired, and eventually became a full time, tenure track professor. Ingram says that his aforementioned affability was not always his signature style as a teacher; coming in as a young professor, it was more reminiscent of “the Davidson that I went to,” in which students were rigorously trained and it was achingly clear how much was expected of them. He has now evolved into a teacher who is simultaneously rigorous and unlikely to provoke anything resembling a nervous breakdown in his students.

It’s a classic Davidson story: a young man came to campus somewhat unsure of himself, a player on the (club) football team who excelled in chemistry, but through the interdisciplinary nature of the curriculum became a Shakespeare fanatic. After obtaining a PhD at Emory University, he returned to that same campus less than a decade after graduating, going on to establish and inspire that same love and enthusiasm for language arts in innumerable students for the next three decades. Davidson’s English department will be different without his presence, but that presence will be felt in the college’s halls for a long time.

How will he be spending his retirement? “Hiking, spending more time outside. A student recently told me that it’s an insult to tell someone to ‘touch grass,’ but it’s advice I take seriously.”

Naturally, the love of reading is not going anywhere. Newly retired, he will get the chance to use weekends that would have otherwise been spent grading WRI 101 papers (an activity that he undoubtedly cherishes) on unpacking labyrinthian tomes such as Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. Will he miss his job? True to form, he thinks of the students: “I’ll miss how much I learn from conversations with [them],” and how the classroom can make a book or a play that he has seen and/or read dozens of times seem new somehow.

As if speaking for many years of students, Hawgood puts it succinctly: “God I’m gonna miss that guy.”