Aidan Marks

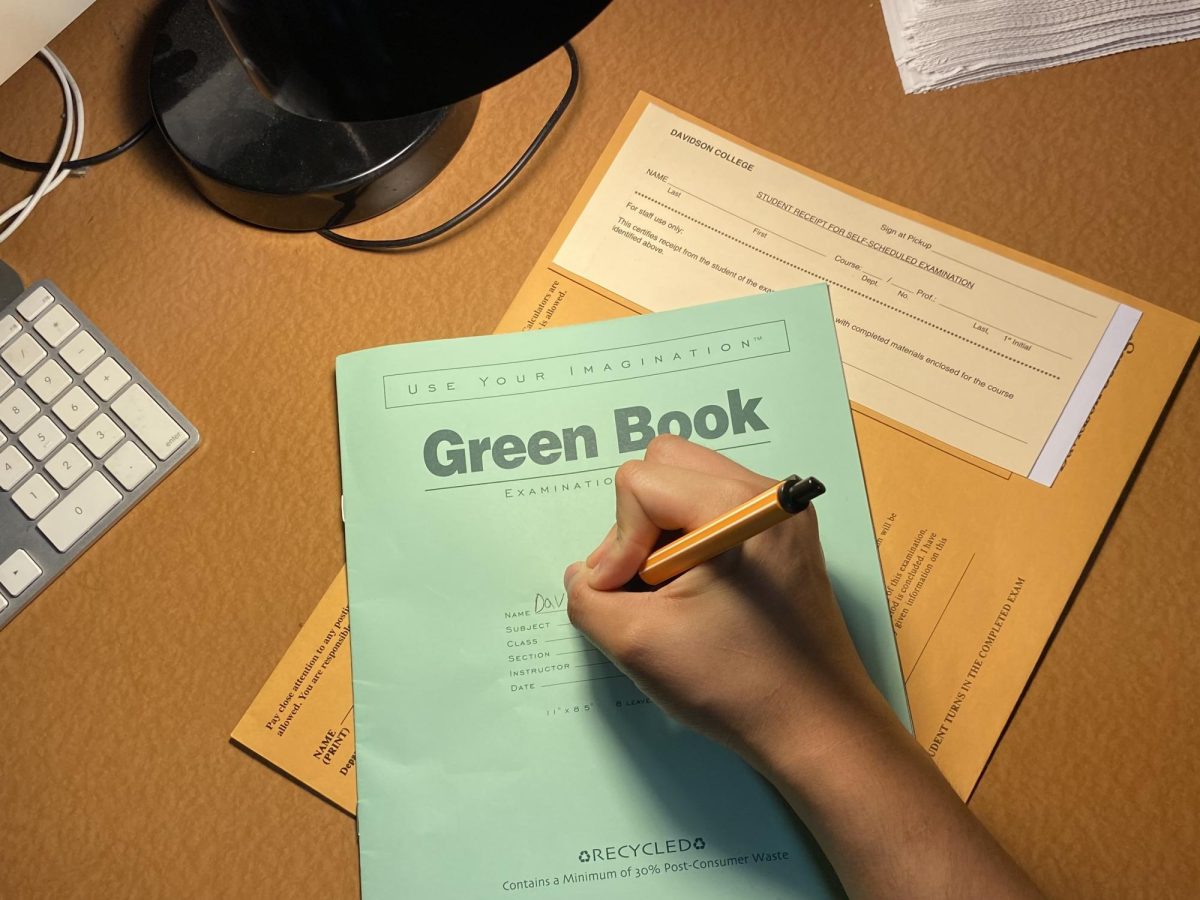

A student uses a green book for an assessment.

Associate professor of biology Mark Barsoum’s Human Physiology class looks different this year. After years of mounting concerns that students in the upper-level biology class were offloading the homework-heavy course’s assignments to AI, Barsoum drastically changed his approach to the class this fall.

In the past, Barsoum placed a heavy emphasis on homework assignments and avoided giving tests. This year, the 38-student class dominated by seniors on the pre-med track is built around in-class problem sets and, for the first time, 25-minute oral exams.

Barsoum is one of many professors at Davidson who shifted to in-class assessments in recent years amid widespread concerns about cheating and AI use.

For the first time in his 43 years at Davidson, Richardson Professor of Political Science Brian J. Shaw is assigning in-class essays in his classes. He referred to last year, when he caught several students using AI, as a “wakeup call.”

“Last year, I had more encounters with plagiarism, all in the form of AI, than I had […] for the previous two decades,” Shaw said.

Shaw, like many other professors, prefers to give his students take-home exams. But he said he felt something had to change. As growing numbers of professors abandon the take home, some professors raised concerns about what the shift means for student learning and the state of academic integrity at the College.

Some professors, like Assistant Professor of Art Lyla Halsted ’14, are using a combination of assessments to deter cheating. In addition to research papers, Halsted assigns handwritten in-class “formal analysis” papers and, like Barsoum, has started to assign more oral exams.

Halsted’s goal with oral assessments is to make sure students can explain and defend the work they submit. “Even if a student were to use […] AI to produce work, when they are presenting it and asked about it in class, they often cannot answer those questions,” Halsted said.

Halsted said that art history may be less vulnerable to AI use, especially for formal analysis papers or in emerging fields with little pre-existing scholarship. But she has had to adapt nonetheless.

That adaptation—especially the move away from take-home essays—is often done reluctantly.

“I would like to assign more papers,” Halsted said. “There is a tension between the importance of students learning how to write in an art historical voice, which is a unique kind of perspective […] and the difficulty of detecting AI.”

Shaw said take-homes are uniquely valuable in the political theory classes he teaches. “Rather than having students memorize […] you have a week to think about it, and you know, hopefully by the time you finish the review, you know more than you did when you started,” Shaw said.

He hopes in-class exams will be a temporary adjustment. “I hope that I’m not going to feel that I need to keep doing what I’m doing now.”

Daniel Layman chairs the philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) department. Layman has used in-class blue book exams since 2023 after hearing stories of rampant cheating in his colleague’s classes and mounting suspicions of his own.

However, he said take-home essays are a better method for assessing student learning and expressed concerns about the limitations of timed in-class assessments.

“I didn’t really feel great about [blue-book exams], because although they are really good at preventing AI use, they’re actually not that pedagogically great for students who are doing the work,” Layman said. “So there were a lot of costs to using that model, and I didn’t like that at all.”

Layman came up with his own method to detect and deter AI use. After reflecting on how he could assign take-home exams while being confident that students are doing their own work, he settled on “self-comprehension quizzes.” Students will be required to reconstruct their argument—handwritten, in-class—a few days after each essay is due.

Layman said this approach specifically targets one of the most pernicious consequences of AI use, which is that “you can produce the product without in any way comprehending or being able to […] retrace your steps through a structure of reasoning.”

Other professors are using a new Google Docs extension, Process Feedback, to monitor the writing process. On the other side of the academic spectrum, professors in mathematics and economics frequently administer assessments through the Quiz Center which allows students flexibility in deciding when they take a test.

Assistant Professor of Mathematics and Computer Science Ana Wright said the Center embodies the Honor Code’s principles of flexibility and accountability.

“Students still can still come in when they want to. There’s flexibility, which I think is in the spirit of the Davidson’s Honor Code, but they’re also in the room with other students so they can hold each other accountable, which I think is also the spirit of the Honor Code,” Wright said.

That accountability, Wright said, is important for two reasons. First, she said her perception is that fewer violations are being reported by students.

“When I talk to people who are nostalgic for the historical Honor Code culture, they often talk about how students would hold each other accountable to the Honor Code […] my impression is that almost all honor code violations are reported by faculty,” Wright said.

Second, Wright said that the proliferation of AI—and the widespread concern that peers are using it—might tempt students to cheat in the name of keeping up with their classmates.

“There’s a lot of competition among students, and if they’re thinking that even one student in their class could be using these tools and everyone is taking a high stakes assignment individually, I just can see that even the most honest student would feel very compelled to use an AI tool,” Wright said.

The idea that group settings facilitate accountability is not a new concept. It also underpins Davidson’s Exam Center, which allows students to schedule when and in what order they take final exams—within parameters set by the College.

To Barsoum, the Center is proof that academic freedoms and accountability structures can coexist. “We’ve always had guardrails in place for students to work within a really robust Honor Code,” Barsoum said.

Those guardrails change over time. “Enforcement has looked different […] in the past, than it does now,” Barsoum said. “That is a reflection of the shift in many elements: shift in culture, shift in student experience and background throughout their lives, and a shift in technology […] in particular because of generative AI.”

AI is not the only reason why some professors worry that academic integrity is suffering. Halsted said perception of the Honor Code is a lot different today compared to when she was a student. In particular, awareness of what the Code actually means and requires of students seems to have taken a hit.

“I don’t remember anyone questioning it, and I don’t remember students being dissatisfied with it. I also remember students being more aware of it,” Halsted said.

Whether attributable to AI, Covid, or any number of causes, professors and students agree that something—whether the perceived lack of trust in students or adherence to the Honor Code, or both—needs to change.

Honor Council Chair Maggie Woodward ’26 said this year is an opportunity to preserve and rebuild trust. “I think we’re in a really unique position to be able to make sure that faculty’s trust isn’t yet broken, and I think it has the potential to be if we […] let outside norms and technological trends impact the way that we operate academically,” Woodward said.